Pamela and Stephen Hootkin

Since the early 1980s, Stephen and Pamela Hootkin have been collecting contemporary ceramics and ceramic sculpture. While they began collecting ceramic vessels, by the end of the decade they moved toward an edgier kind of work, with narrative content and strong psychological and existential overtones. Along the way, they befriended many of the artists they collected and formed deep and lasting relationships. Highlights of the collection include works by Robert Arneson, Beth Cavener, Viola Frey, Peter Gourfain, and Michael Lucero. Their vision in forming the collection was incredibly cohesive and focused. Stephen is an alumnus of UW–Madison, graduating with a BS in political science in 1964.

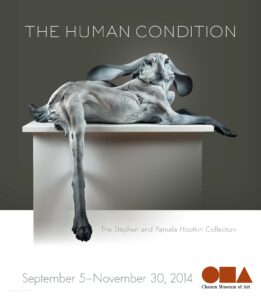

In 2014, the Chazen Museum of Art exhibited the Hootkin’s collection in The Human Condition: The Stephen and Pamela Hootkin Collection of Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture. Portions of the collection were donated to the Chazen Museum between 2012 and 2017 and the remainder of the collection is a promised gift.

“Stephen and I are both very visual people. Without deep pockets early in our career, we didn’t have a big budget for art. As we went to galleries, it seemed that our tastes in two-dimensional art were not always in sync. One afternoon, we happened to be walking through Soho and stopped in a gallery called Convergence, which was owned by Don Thomas and Jorge Cao. There was a show of work by Bruce Lenore. He was a young man from RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] who made vessel forms, beautifully glazed raku. We walked through the show and at the end we compared notes and found we liked the same piece. We realized that for some reason—whether it was the three-dimensional form, whether it was the ceramic medium or the combination of the two—we both reacted visually to the same thing. We loved the color, loved the depth of the glazes, the forms, and the material. We bought a piece from the show, which we still have. That’s how we started.” –Pamela Hootkin

Q: Is your entire collection on display, or do you have some works in storage?

P: Not everything is on display. The totality of what we own of ceramic pieces is closer to 300-plus. There are many pieces on view at the Chazen, and in our loft…We have these John Gill vases—12 or 14 of them—and when I was working, I had them build shelving in my office and displayed them there. It was a joy to be able to sit across from them at work every day. There are pieces that we’re still attached to but don’t have space for and are still in storage.

S: There are some larger pieces that we bought knowing we would never have room for them in our loft—Humiliation by Design and L’Amante by Beth Cavener, and The Fools’ Congress by Arnold Zimmerman. We shipped them directly to the museum.

P: Even if we didn’t have space for it, nothing stopped us from collecting.

The Hootkins live with their extraordinary collection of contemporary ceramic sculpture in their New York City loft.

Q: Have you ever collected based on specific spaces in your home that you were looking to fill?

P: No. We never said, “Oh we need a pink painting over the couch.” We always responded to the work and then brought it home and figured out how we could integrate it into what was already there.

S: We spent days or weeks moving things around when we bought a new piece to make sure it fit in holistically with the entire collection. Fit in but didn’t disturb anything. We spent tons of time making sure it is just perfect in our eyes.

P: What is interesting in that process is that when you bring a piece in to your home you then begin to notice how it speaks to other pieces in the collection—in form, color, shape, structure or aura. That was a very interesting outgrowth of acquiring new work, seeing the existing pieces in a new light.

“Cabbage Man” and other shard sculptures by Michael Lucero, along with “Torsos” by Judy Moonelis keep the Hootkins company.

Q: What is the “strangest” place you have displayed artwork in your home?

P: We have a work in our bedroom of 10 torsos by Judy Moonelis which she made after reading letters from her father, who had freed people from concentration camps in Germany. The context of the pieces is heavy and sleeping with something above your head may be deemed a little strange. That, coupled with the fact that we have 4 of Michael Lucero’s hanging shard pieces—the Devil on one side, Jesus on the other and a few others for good measure—people have come in our bedroom and said “I can’t believe you sleep in that room, you must be very well adjusted!”

Q: Has there ever been an accident with a work in your collection?

S: In a previous apartment, while I was sleeping all of a sudden I heard a crash and woke up and said “Oh my god! Oh my god!” One of the pieces—Cabbage’s Revenge by Michael Lucero—had fallen to the ground and shattered some of the leaves. I was totally upset! (The piece has since been meticulously restored).

P: We’ve had other small incidents, and we have come to learn that it is part of the delicate medium [of ceramics].

Q: The display of artwork in your loft is pretty dense. It might be hard for someone who doesn’t collect art to imagine living in a home full of all of these wonderful, and delicate, 3-D pieces.

P: That’s one of the greatest things about living with this work. You live with it and can engage with it at any time. When we built the loft and moved in before the artwork came over, Stephen had the shakes. He could not stay in the apartment because there was no art in it yet. For one day in the empty apartment I said, “This is great, it’s like being at a spa, it’s so zen.” But we both missed the art.

Q: Is there a work or an artist that has surprised you in their notoriety since acquiring them?

S: We didn’t realize that L’Amante would be so popular and become one of the most asked-about works at the Chazen.

Q: Do you have any memorable experiences from acquiring a work of art in New York?

S: Yes we do. But back then the East Village was a very difficult place. There were a lot of drugs, vacant buildings, and empty lots. I came from my office wearing a suit. I got off the subway and started walking towards Avenue B or C. A policeman stopped me and said, “Where are you going?” I said I was going to see my friend. He said, “Let me escort you. You shouldn’t be walking around here wearing a suit.” So the next time we went to visit Michael Lucero’s studio we put on our torn blue jeans. I put money in the bottom of my sock, we put on our oldest clothes and we walked through that neighborhood. That’s just a little aside of how far off the beaten path we were willing to go to visit our artist friends.”*

Q: What advice would you give to new, or aspiring, collectors?

S: Follow your heart. Don’t listen to anybody—a gallerist, a friend, anybody else. Just do what you like. It takes a while to build up confidence and buying based on emotional connection, not just what someone else tells you is great.

P: We trusted our own instincts and always bought what we responded to, so it made (the collection) cohesive when it all came together.

Q: Do you think sharing your collection helps people to better understand you as individuals?

S: Every once in a while, someone in Pam’s office or my office would come over and they could not reconcile how we looked in the corporate office and how we looked with, what they called, “stuff” in our home. It took them a while for them to adjust.

P: It balanced our lives—corporate suits on the one hand, and our relationship with artists and living in the art world on the other.

Q: Do you have any favorite works in the Chazen’s permanent collection?

S: The Lane Collection is, for us, the most important collection at the Chazen. Having the finished works alongside the behind-the-scenes material is extremely important historically, visually, and for the Chazen’s education mission. We always walk through those galleries when we visit.

P: Also, Zelda [Untitled #1378 (Zelda Fitzgerald)] by Petah Coyne. I could stand and look at it for a long time and marvel at it visually and conceptually in terms of her process. It’s a masterpiece.

*Portions of the Q&A include excerpts from The Human Condition: The Stephen and Pamela Hootkin Collection, which can be purchased at the Chazen Café.

*Portions of the Q&A include excerpts from The Human Condition: The Stephen and Pamela Hootkin Collection, which can be purchased at the Chazen Café.