by Sophia Abrams ’22

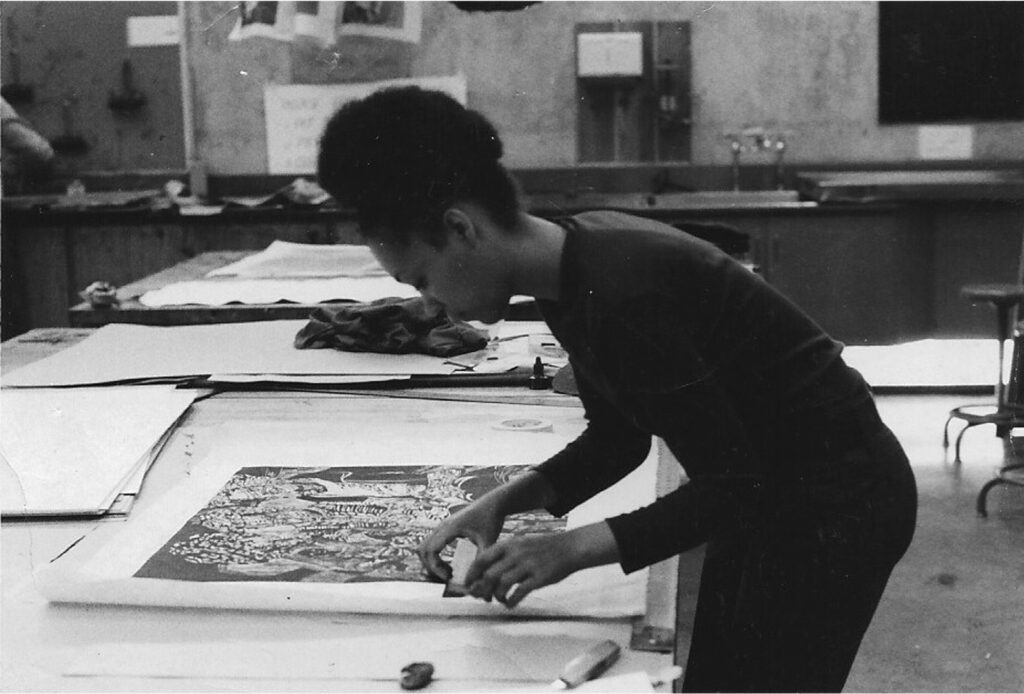

The year is 1971. Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” oozes soulfully from the radio. On the sixth floor, in the relief printmaking studio of the art department in the Mosse humanities building, Freida High Wasikhongo Tesfagiorgis stands over a printmaking table, preparing for her Master of Fine Arts exhibition. That same year, she accepted the artist-in-residence position in the new Afro-American Studies department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Her afro is pulled to the top of her head in a puff. Her eyes concentrate on preparing to mat a woodcut print. Peers work in the background, grabbing tools as needed. Wearing solid colors, she measures her decorative figure print.

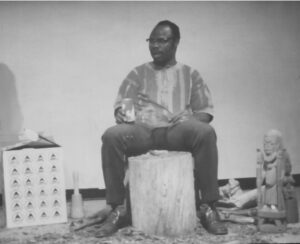

ARTIST: Freida High preparing to mat a woodcut print, Relief Printmaking Studio, Art Department, 6th floor Humanities Building, UW-Madison, ca. 1971. Photo from F. High files.

“I found the art department very exciting, [particularly considering] my major professor [Ray Gloeckler, a dynamic printmaker],” High remarked from her Madison home over a Zoom interview on July 2, 2021, her afro puff still intact, fifty years later.

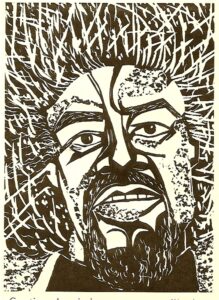

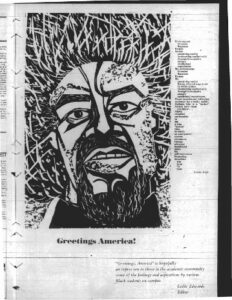

Two years earlier, as a first-year graduate student, her woodcut Greetings, America greeted Daily Cardinal readers as the December 2, 1969, issue focused on Black students on campus. Prominent sharp, thick lines in the woodcut reminiscent of Elizabeth Catlett’s Sharecropper, create a Black man whose eyes lock with the reader’s and his afro jets beyond the corners of the print.

Freida High, “Greetings, America,” 1969, woodcut, 15 x 11 in, courtesy Freida High

Daily Cardinal student newspaper, UW–Madison, Dec. 2, 1969

The issue was the product of the past year’s February 1969 Black Student Strike, which was tumultuous for some, and victorious for others. Now the demands of Black students were freshly seared into UW–Madison’s collective memory, and the momentum was building like an archer about to release the bow, knowing that it would hit the bullseye.

As UW–Madison welcomed back students and the fall 1969 semester commenced, High decided to attend a Black Student Union meeting in the newly opened Mosse humanities building’s auditorium. The Afro-American Studies department had gained administrative approval as a result of the 1969 Black Student Strike and negotiations, but awaited an official department. Inside, she was involved in a discussion of student representatives to serve on the Afro-American Studies steering committee. The steering committee was responsible for detailing the requirements for the major in Afro-American Studies and searching for faculty for the department.

Students who were interested in joining the steering committee were asked to stand, introduce themselves and state why they were interested. High recalls telling the crowd that she was interested in seeing where the department goes, emphasizing that she had been involved with the Black Student Movement on campus at Northern Illinois University as an undergraduate. At NIU, she was a founding member of the Afro-American Cultural Organization (AACO) and served as the historian on the executive board. She also initiated and played a large role in organizing the Black Arts Festival in LeClaire Courts in Chicago (then public housing for World War II veterans and their families) where she grew up. At Madison, she was one of the two graduate and five undergraduate students (one an alternate) who were chosen to be on the steering committee, helping to establish the department she would eventually work in for over forty-one years.

This was not High’s first soiree with activism, let alone in Madison. A child of the Great Migration, High’s life encountered the necessity of activism, as injustice undulated in direct and indirect pronouncements. The oldest of 12 children, High was born in 1946 in Mississippi and migrated to Chicago when she was six years old. Immersed in the arts when possible, much of High’s childhood revolved around family responsibility. High started college at Graceland College (now University) in Lamoni, Iowa, and transferred to Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, graduating with a degree in art education. Inspired by the Black Arts Movement in Chicago, where she had her first solo exhibition at the South Side Community Art Center that same summer, High moved to Chicago and taught at DuSable Upper-Grade Center (middle school) one semester, then worked in Neighborhood Youth Corp as a job developer in Rockford, Illinois. Importantly, before enrolling at UW–Madison for graduate school, High student-taught at DuSable High School under the supervision of Dr. Margaret Burroughs (chair of the art department) and Mr. Ramon Price. Dr. Burroughs was co-founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History and the South Side Community Art Center).

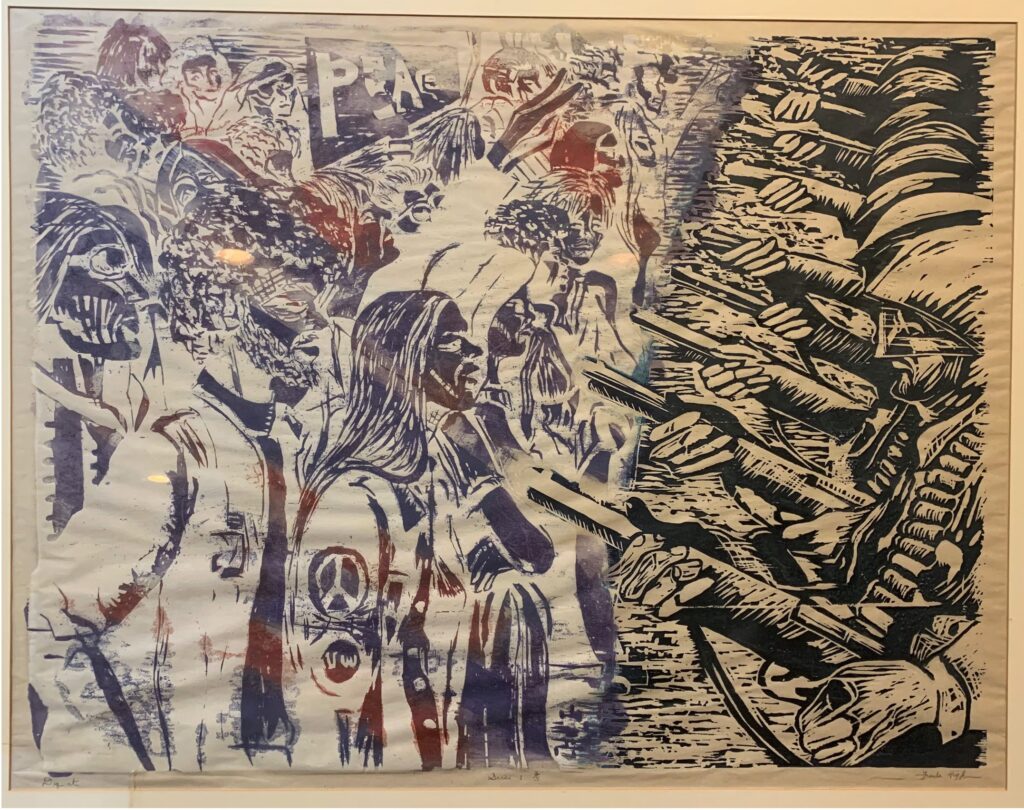

Also, in 1969, High participated in the Women’s Welfare protests at the Wisconsin State Capitol. Stimulated by the bold imagery stirred by the protest, High created the print Dig It highlighting the tense scene of students versus the State and the National Guard. The carved black and white contrasts of the guards and civilians brushed in red and blue draw viewers in. In the corner of the woodcut, “PEACE” is incised on the print.

Freida High, “Dig It,” woodcut, 1969, 23 x 30 in., shown under glass, courtesy of Kwame Salter

As a graduate student, High’s work encountered mixed responses.“The responses from [some] students were often disturbing because this ridiculous question would [often] come up: ‘Why are you painting Black people, or why are your subjects Black?’ It never occurred to them that they were painting white subjects. That’s something that could get on your nerves, but I focused on my work,” High said, remarking on a tension that Black artists still encounter today.

This is an aspect of the conflict that created the foundation of High’s time at UW–Madison; however, most importantly, Black students reinforced and empowered each other in discussions and debates on the Black aesthetics, critiques of each other’s works, organizing of exhibits, etc.

Within a year of graduating from UW–Madison in 1971, High was hired as an assistant professor in the Afro-American Studies department and art department to develop African and African-American art curricula. First on her agenda was centering and creating two art history classes (“Introduction to Traditional African Art” and “Introduction to African-American Art”), and a graduate art seminar for the Afro-American Studies and art departments.

To develop this curriculum, High continued to conduct research on African and African-American art history. Drawing on her study of African art at Indiana University, the influence of her mentor and teacher Roslyn Walker, and the larger influence of the Roy Sieber School, High had a robust foundation. Additionally, in the area of African-American art, she drew on Modern Negro Art by James Porter, exhibition catalogues of E.J. Montgomery, the intellectual exchanges of the National Conference of Artists, the art collections, resources by Alain Locke and Samella Lewis, and the encouragement of Dr. Margaret Burroughs.

Working with the Afro-American Studies department to create the courses, High created a curriculum that enabled students to understand the constant dialogue between artists and art historians across time and space. Like an innovative climber scaling a mountain of promise and reward, she frequently ascended up Bascom, advocating for specific resources to enhance the Afro-American Studies art history curricula.

“The administrators were very important because I found that the deans were very supportive of African-American Studies in terms of providing facilities. If I wanted to travel to take the students to this exhibit in Chicago or to take them [to] Washington D.C., I had that kind of support,” High said of the College of Letters and Science, where the Afro-American Studies department is located.

Starting with the foundation of Modern Negro Art, “Introduction to African American Art” organized the chronology of Black art from American slavery to contemporary art. It presented Black art in a national climate that historically undermined and belittled the existence of African-American art and artists. Most critical is the positive aspect of the course. It introduced students to a history of art created by enslaved populations and free African Americans, inclusive of African retentions, and spanning period styles of Neoclassicism, Romantic Realism, Impressionism, Modernism, developments of the Harlem Renaissance, the Works Project Administration, the Civil Rights era, the Black Arts Movement, and later Feminism. She moved students, especially Black students and women artists, with the arts’ affirming and rousing sensibilities.

In 1970, after graduating with a BS in art education from Jackson State University, Jerry Butler (MFA ’72) moved to Madison to pursue his MFA in painting. As a graduate student, Butler painted stirring portraits of Angela Davis and Malcolm X that were poorly received by his peers and faculty. In an art history class, his professor failed him despite Butler’s meticulous preparation for the course. While the Afro-American Studies department was created, Black students still faced exclusion in and outside of the classroom. Notably, High’s classes on African and Afro-American Art served as an inspiring space for Black students.

“In that course, I realized that I wasn’t going to be the first African American artist. I found out that [there] were tons of people who were African-American artists,” Butler said, who is still based in Madison and continues his artistic practice.

•

Given High’s dedication, she frequently wrote proposals to invite Black artists to give lectures at UW–Madison and collaborated with other departments. In the early 1970s and later, abstract color field painter Sam Gilliam (guest of the art department and collaborator with Bill Weege) arrived at UW–Madison in bell-bottoms and gave inspiring lectures that left students floored by his postwar painting technique. Just as Gilliam transformed painting’s canon in 1965 with his intentional draping of canvas as opposed to stretching the canvas on stretcher bars, he now was a part of a cohort hand-selected by High, whose artistic practice encouraged art students to think out of the box when approaching their own practices. Simultaneously, Gilliam gave Black students great pride, hope, and determination in High’s seminar and the larger campus. Continuing High’s 1970s colloquium-style series of giving students access to artists and their intoxicating art ethos was Benny Andrews. In 1973, in a tweed jacket, the figurative painter lectured in the large lecture hall in Mosse, visited the art department and talked to students in the art gallery with lingering cigarette smoke. Still an essential asset of the art department, the colloquium hosted—and variably co-sponsored with the art, African Studies, art history and Visual Culture department—other guests, such as David Driskell, E.J. Montgomery and Lowery Sims.

Yoruba sculptor Lamidi Fakeye

The diaspora’s connections permeated through cross-cultural artistic exchanges. Lamidi Fakeye, a Yoruba sculptor of Nigeria, sat in the Seventh Floor Gallery, Orange Crush soda in hand, giving a demonstration on indigenous carving techniques. Wearing browline glasses and a dashiki, he answered questions as wood shavings showered the floor like a snowstorm gradually covering a city’s landscape.

In 1972, High stands before a Suku helmet mask of the Congo, reviewing it while installing Traditional Art of Sub-Saharan Africa. The gallery door is ajar, welcoming Madisonians into a world far beyond the Midwest. Rich African textiles spanning from Mali to South Africa drape the walls, each decorative in symbols that undulate through the textile prints.

During another one of his many visits to UW–Madison, Sam Gilliam remarked to High, “You should not be doing this alone,” as she installed the show. This sentiment served as a seminal teaching moment for High’s respective teaching and curatorial practice.

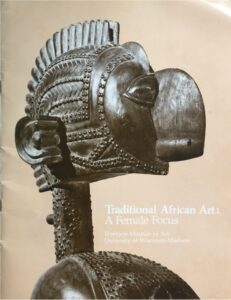

From October 2 to 29, 1972, one hundred works of masks, figures and textiles were on display at Memorial Union’s art gallery. Nine years later, this research expanded to Traditional African Art: A Female Focus, the first African art exhibition at the Elvehjem Museum of Art (now the Chazen Museum of Art). This time High was assisted by visiting Ghanaian artist Kweku Andrews (a graduate student in art education) to collect and organize the show and catalog. Elemental in this collaboration was High’s utilization of an assistant and museum staff to organize and install the exhibition.

“Traditional African Art: A Female Focus”

Curator: Freida High-Wasikhongo, assisted by Kweku Andrews, Elvehjeum Museum, 1981

Women and the African diaspora’s communities descended from people indigenous to Africa were coming to the forefront of High’s practice. In 1983, High coined the term “Afrofemcentrism,” which revolves around critically assessing Black women’s artwork and intentionally focusing on the intersection of race and gender.

As an undergraduate student at NIU, High once asked her professor why there were no Black artists taught in her art history class. Her professor remarked, “There are none.” Taken aback by her professor’s answer, High approached her professor after class to discuss his answer, and they agreed she would research Black artists who could challenge this claim. Since that integral moment, High adamantly challenged the canon’s Eurocentrism and the art world’s lack of Black art with her research. She stepped into a role and ignored those who challenged her emphasis on Black art within the context of the development of Black Studies, Women’s Studies, and other movements and related curricula in higher education. In the 1990s, with her expanding interest in modern art and Primitivism and the rise of the new visual culture studies, she entered the art history PhD program at the University of Chicago to bring such knowledge into UW–Madison curriculum, such as graduate courses on visual culture.

As the years progress, research in Black art expands: with each coming year, the practice of Black art broadens, infinitely expanding the definition of what constitutes Black art. This is seen in High’s practice. Her insight and precision demanded to broaden what African and African-American art could be. When she initially developed the curriculum in the early 1970s, she focused on teaching students a comprehensive history of African-American art, with courses, such as “Contemporary Black American Art: History and Criticism.” Simultaneously, during that time, High conducted research in Nigeria on a Vilas Fellowship, introducing contemporary African Art into Afro-American Studies. In the 1980s, High created courses such as “Art History Artistic/Cultural Images of Black Women” and “Contemporary Black American Art: History and Criticism” in the Afro-American Studies Department. In the 1990s, she taught a museum studies course that mentored students in curatorial practices, such as the 2010 “Artist Book Exhibit.” This is also seen in the gradual classes of Black student artists at UW–Madison, each creating a distinct practice wholly unique to the individual artist.

“Freida High was my professor. I’m very honored and grateful to have been in her physical space and to have been nurtured by her,” remarked Tyanna Buie, a 2010 MFA printmaking student, whose practice galvanized imagery of childhood and Blackness. In 2010, Buie met with co-curators of African and African American Artists’ Books and Children’s Book Artists at the Kohler Art Library, contributing to the categorical themes of the exhibition, and designed the brochure for the exhibition.

Retired since 2012, High continues to be active in the Madison art community, and her legacy at UW–Madison endures. “Introduction to African American Art” is still taught, now by Professor Melanie Herzog. The seismic weight of Afrofemcentrisim permeates through generations, implicitly and explicitly manifesting through canonical work. In 2016, MFA student Jay Katelansky’s thesis show was no exception.

High’s success was never isolated. It was predicated on collaborative work, support, and enriching exchanges. At UW-Madison, it was illuminated through interaction with and support of administrators, faculty, staff, and students that started with the College of Letters & Science, and included faculty/administrators in Afro-American Studies, African Studies, art, gender & women’s studies, art history, the late director of the Elvehjem Museum of Art Katherine Mead, curators, and staff at the Elvehjem/Chazen Museum of Art, staff at Wisconsin Union Directorate. Notably, Professor Henry Drewal was especially essential after he joined Afro-American Studies and art history in 1990 and developed new African and African diaspora courses, exhibitions, and the African Art gallery at the Chazen Museum of Art. High and Drewal shared many of the same undergraduate and graduate students. At times, they collaborated in teaching, symposiums, and bus tours with their students to museums in Chicago and Milwaukee.

As a professor, High’s students were especially significant to her pedagogy, with their many dynamic questions and debates, research papers, art projects, theses, dissertations, and MA and MFA exhibits. Students were critically significant to High’s work as she taught, curated, created art, published, collaborated on conferences and symposiums, and expanded African and African American art history over the years.

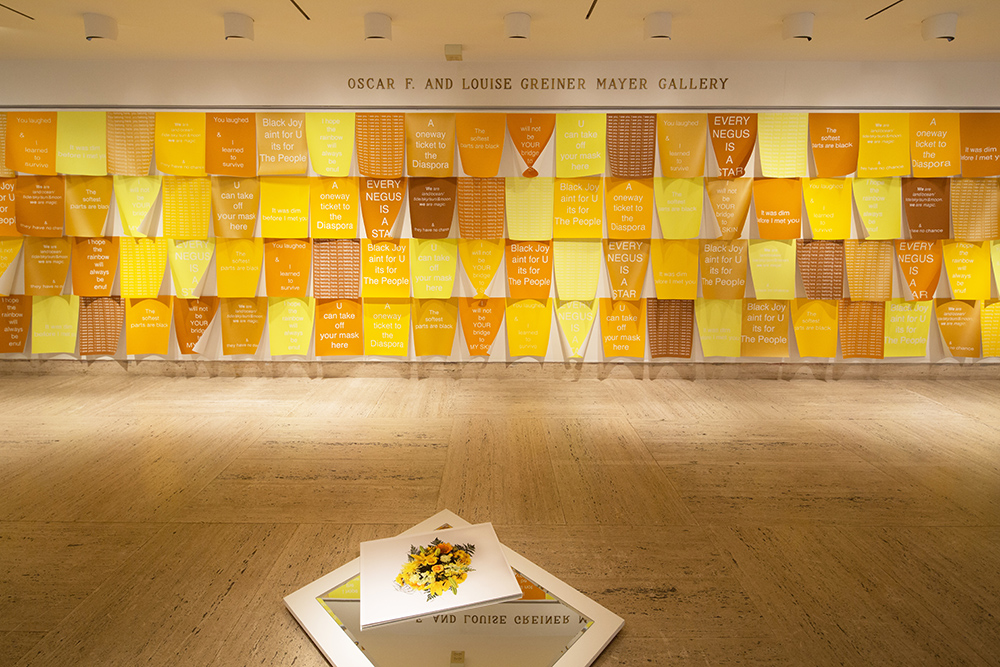

Walking up the stairs in the Chazen on April 15, 2016, the smell of soul food and jazz music greets museum-goers. At first glance, it appears that one is walking into a birthday party: rainbow confetti is thrown to the ground, making one wonder if they have come to the party too late. Golden balloons spelling out “Won’t U Celebrate” are anchored to the floor with Arizona Iced Tea cans drawing one into the center of the room. Music from the band outside of the gallery lingers. A cake sits with a Polaroid photo printed on it and confetti sprinkled around the perimeter. Children are pushed in strollers, and their parents slowly digest the grave content splayed across the exhibition.

Jay Katelansky’s Panczenko Prize exhibition

In the gallery, a wall of lemon-meringue yellow posters transform the Chazen’s white wall like roof shingles protecting a house to assuage Blackness with affirmations like “the softest parts are Black.” In the corner of a gallery, Gloria Gaynor’s 1978 I Will Survive transcends time and reverberates through gallery-goers eardrums via wall-mounted headphones. Turning ninety degrees in the gallery, two television screens fixed to the wall show videos of two Black women laughing. This is the opening night of Hoodwinked, Jay Katelansky’s 2016 Chazen Prize for an Outstanding MFA Student, Katelansky’s three-year practice at UW–Madison culminating into a striking MFA Show that delicately explored Black death and celebrations.

“Invisible Man helped me hone down [my MFA show]. The book talks about how the invisible man has a hole that he goes to, and this hole is not dark; it’s filled with lights. But he explained it as a warm, welcoming place where he goes to feel safe. I wanted to create something that brought that light to a wider range of people,” Katelansky said in June 2021 from Oakland, California, sunlight shimmering in through her window, illuminating her afro’s subtleties of texture and color.

As Katelanksy radiated under the aura of her thought-provoking work and literally ascended into the physical space of the Chazen, her work was predicated on the ethos of High’s commitment to and centering of Black artists, especially Black women artists. Since High graduated from UW–Madison in 1971 and subsequently embarked on her dual practice of being an artist and professor, over thirty-five Black artists have graduated from UW–Madison. This number is a grain of salt compared to the UW–Madison student population of over 40,000 in 2021. However, like High, this unique cohort of artists has paved roads for themselves that jet across the expanse of time and space. They are creating art that situates itself as a necessity of each artist’s praxis that often elucidates sentiments pertinent to the community at large.

Now a network of Black student artists who attended UW–Madison create their roots across the country, connecting like a constellation in the night sky radiating from millions of miles away. In Philadelphia, 2015 graduate Alex Jackson’s studio pumps out paintings that merge Alma Thomas’s exuberant, colorful style with Kehinde Wiley’s hyperrealistic African American portraits adorned in Victorian backgrounds. In Washington D.C., 2020 journalism major and art certificate student Shiloah Colely expands her painting and woodwork practice as an MFA student at American University, anchoring the community in her often autobiographical work. In Oakland, Jay Katelansky continues to create art that centers and affirms Black softness. First Wave scholar Auzzie Dodson’s practice extrapolates themes of gender and Blackness to create dynamic sculptures and paintings. Expected to graduate in May 2022, Dodson enters an artistic terrain few have the pleasure of frequenting. Still, if one does become one of the few lucky graduates to be a Black art student at UW–Madison, they are obliged to be a part of a rich, complicated legacy that necessitates the importance of Black art as a pillar of society.

High’s legacy increasingly comes to fruition with each passing year as Black art graduates walk across the graduation stage and move their tassels from the right side of their cap to the left. When High started as an assistant professor, Black art and artists lacked academic, cultural, and institutional recognition. Utilizing an intersectional approach to African and Afro-American artists, High radically altered the landscape for Black artists to be celebrated and nourished through her through-provoking curriculum and exhibitions. Now, her ethos and dedication to Black art and respective research ricochet across time and place, inspiring the next cohort of Black artists and curators to explore the infinite possibilities of Black art.

To culminate Abrams’s research on Black artists at UW-Madison, an April 2022 exhibition entitled “Black Expressions” will be on display at the School of Education Gallery to commemorate the history of Black artists at UW-Madison, as well as auxiliary exhibitions at the Kohler Art Library exhibiting the ephemera of UW-Madison Black Student Artists, the Multicultural Center’s Class of 1973 Gallery highlighting current Black student artists and the Madison Public Library’s The Bubbler exhibition paying homage to Black artists in the greater Madison area. In May 2022, the interviews will be publicized on the archives website.