This year, UW–Madison faculty members from disciplines across campus used the Chazen’s permanent collection to spark curiosity, deepen analysis, and make abstract ideas more tangible to students.

Visiting the Chazen’s galleries and study rooms, classes engaged with paintings, sculpture, and works on paper to explore subjects as diverse as nineteenth-century visual culture, environmental humanities, and world history. The impacts lasted well beyond a day’s visit to the museum.

Study room visits are “unfailingly inspiring, fun, and transformative for my students, and so powerfully shape the work we do together for the rest of the semester,” says Sarah Ensor, assistant professor in the English department.

Seeing Climate Change Through Art

In English/Environmental Studies 153: Introduction to Environmental Humanities, Ensor’s students considered how art, literature, and film can deepen understanding of environmental crises. One visit to the Chazen invited them to approach artworks as primary sources, documenting their observations and drawing connections to key course themes.

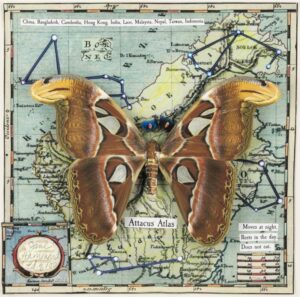

Jane Hammond (American, b. 1950, Atlas, 2022, digital inkjet print with rice paper, methyl cellulose, acrylic paint, modeling paste, peacock feathers, and archival foam core, Jade glue, and graphite, 9 3/4 x 9 3/4 in., gift of the Madison Print Club, Madison, Wisconsin, 2023.26.2

“In this most recent visit, I loved watching one of my students, an entomology major, spend forty minutes with a classmate looking at Jane Hammond’s 2022 work Atlas, which complexly plays on the image of a moth pinned behind glass,” Ensor said. “It was so inspiring to see her bring experiences from her other classes and labs to bear on this one, and to watch, too, as she let her own presumptions about her field be complicated as she saw it given back to her in new terms.

“Part of what I love about the Chazen is that it meets my students and me where we are—in our passions and interests and fields of knowledge and habits of attention—and then inspires us to make something new with, and of, them, by virtue of our conversations over these amazing works of art.”

Portraits of Power in Austen’s England

Dr. Amanda Shubert’s English 345: The Nineteenth-Century Novel brought students face-to-face with the visual culture of Jane Austen’s world. As the class read Pride and Prejudice, they visited the Chazen to study early nineteenth-century English watercolors, beginning with a slow-looking exercise that encouraged deep visual analysis.

John Scott (British, 1850–1918/1919), Woman Seated in an Interior, n.d., watercolor, 16 1/8 x 10 7/16 in., gift of James Jensen, 1994.82

John Rubens Smith (American, b. England, 1775–1849) Portrait of Joseph Ellis Bloomfield (1787–1872), ca. 1818, transparent and opaque watercolor on paper mounted on thick card, 10 1/2 x 8 1/2 in., gift of D. Frederick Baker from the Baker/Pisano Collection, 2018.14.42

Students focused on two portraits with stark contrasts: one, Woman Seated in an Interior, formal and decorative; the other, Portrait of Joseph Ellis Bloomfield, a dark, commanding portrayal of a man who dominates the frame. The class used these comparisons to spark discussion about gender, class, and power—themes that also permeate Austen’s writing.

“Looking closely at objects teaches students fundamental skills of observation, description, analysis, and contextualization—the building blocks of literary interpretation,” Shubert said. “Taking students to the Chazen also builds their confidence in cultural spaces like museums, which can seem inaccessible to people who did not grow up in families that used or felt welcome in such spaces.”

Tracing Global Histories Through Objects

In HIST 130: An Introduction to World History, History Lecturer Paul Grant used a Dutch oil painting and an African religious sculpture from the Chazen’s collection to explore how global encounters are reflected in art, analyzing them through themes like trade, religion, and cultural exchange.

Frans Jansz. Post (Dutch, ca. 1612–1680), Village of Olinda, Brazil, ca. 1660, oil on canvas, 32 1/2 x 51 1/2 in., gift of Charles R. Crane, 13.1.16

One painting, Village of Olinda, Brazil by Dutch artist Frans Jansz. Post, shows enslaved Africans socializing in the foreground of an exoticized landscape. Another object, a Yorùbá figure clad in cowrie shells, reflects African artistic traditions and complex spiritual symbolism. Students analyzed the complicated significance of cowrie shells, which were used for centuries as currency in Southeast Asia before they were introduced to West Africa by the Portuguese. Much commerce—including of enslaved humans—was transacted in cowries. They later became a symbol of wealth and prosperity in West Africa, especially among the Yorùbá.

Unknown (Nigerian, Yorùbá People), Cowrie Garment (èwù ìlèkè) for Twin Memorial Figure (ere ibéjì), early twentieth century, cowrie shells and fabric, gift of Drs. James and Gladys Strain, thanks to Jerry and Simona Chazen for their generosity to the University of Wisconsin, 2013.52.2

“Many students, especially those in the hard sciences, feel the need to reduce history to a formula that might be solved for zero,” Grant said. “Studying objects makes that approach harder, because students are forced to recognize that life is full of contradictions and complications.”

Grant said his first time bringing a class to the Chazen “went smashingly well. Since the visit, the students really began to take more risks and using their imagination to understand the people we are reading about, who lived in very different worlds. It won’t be my last visit!”

A Living Collection, A Living Classroom

From collage to cowrie shells to canvases, the Chazen Museum’s permanent collection is helping UW–Madison faculty turn their courses into immersive, interdisciplinary experiences.

Want to bring your students into the Chazen’s study room? Learn more about faculty resources, object-based learning sessions, and teaching support at https://chazen.wisc.edu/learn.