We’ve asked our docents to take us on “virtual docent’s tours,” showing us digitally some of their favorite works. Diane Mertens was a high school literature and writing teacher for over 45 years, and to help her incorporate visual arts into her language arts curriculum she participated in workshops and courses sponsored by art museums. She’s been a docent since 2016 and has audited art history courses at UW–Madison each semester for the past four years.

We’ve asked our docents to take us on “virtual docent’s tours,” showing us digitally some of their favorite works. Diane Mertens was a high school literature and writing teacher for over 45 years, and to help her incorporate visual arts into her language arts curriculum she participated in workshops and courses sponsored by art museums. She’s been a docent since 2016 and has audited art history courses at UW–Madison each semester for the past four years.

Mertens’ tour features prominently one of our favorite pieces: Petah Coyne’s Untitled #1378 (Zelda Fitzgerald).

Petah Coyne, (American, b. 1953), Untitled #1378 (Zelda Fitzgerald), 1997-2013, Mixed media including silk flowers, wax, acrylic paint, pearl-head pins, artificial pearls, cast wax statuary figure and hand sculptures, ribbon, knitting needles, fabric, thread, wire, horse hair, drywall, plaster, filament, rubber, steel, wood, 81 3/16 x 35 3/4 x 35 3/4 in., Joen Greenwood Endowment Fund purchase, 2018.39a-b

When you’re conducting a tour of the permanent galleries, which pieces do you always show your guests?

I created an “Art Comes from Art” tour, and, when conducting it, I show Petah Coyne’s work, Untitled #1378 (Zelda Fitzgerald). “Art Comes from Art” highlights interconnections among the arts: the visual arts, the performing arts, and the literary arts. A classic example is Pictures at an Exhibition, a piano suite by the Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky. The suite is based on pictures by the artist, architect, and designer Viktor Hartmann.

Why do you include these particular pieces in your tours?

I am interested in pieces of art inspired by literary works, their themes, and their authors, and enjoy assisting visitors make connections.

I was drawn to Petah Coyne and her sculptures because she is influenced by literature, especially works written by women. In an interview, Coyne commented that her two favorite activities are working in her studio and reading. She has read stories by Flannery O’Connor, Zora Neale Hurston, Joyce Carol Oates, Joan Didion, Charles Dickens, John Steinbeck, and many other writers. During Coyne’s childhood, she lived in a Japanese neighborhood in Hawaii and developed an interest in Japanese literature and culture. One example of this influence is her sculpture, Untitled #1379 (The Doctor’s Wife). This piece, inspired by Sawako Ariyoshi’s novel The Doctor’s Wife, visually illustrates the story’s horrific battle between a doctor’s wife and mother.

In her sculptures, Coyne captures the ambiguities in literature and in human relationships. The sculpture, (Zelda Fitzgerald), is both beautiful and macabre. Zelda is best known as the wife of American writer, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and most visitors know about their romantic yet tumultuous relationship. They envision the couple as an icon of the Roaring Twenties and Zelda as one of its “golden girls.” Some know that she was a muse to her husband and that he even inserted lines from her diaries into his novels, including his most famous work, The Great Gatsby.

However, fewer know that Zelda was a talented writer, artist, and ballerina. When Zelda was in high school, she won a literary prize for her short story, “The Iceberg,” about a daring young woman from an aristocratic Southern family who flaunts convention. This story predicts tensions in Zelda’s own life, especially between her desire for independence and her need for dependence. After Zelda’s separation from Fitzgerald and during her treatment for mental illness, she continued to write and paint.

The materials Coyne uses in her sculpture highlight the complexity and duality of Zelda’s life. The viewer sees strands of artificial pearls, silk flowers, ribbons, a cast-wax statuary figure, numerous cast-wax hand sculptures, and lots and lots of candles that are partially burned down and dripping wax. By encasing this sculpture in a glass cabinet Coyne both enshrines Zelda and pays homage to the beauty and tragedy in her life.

In addition to Coye’s piece, I include the following artworks in an “Art Comes from Art” tour:

- Jim Dine, What was then, will never be again

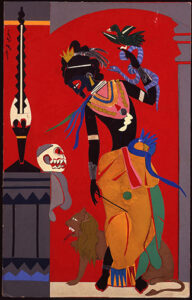

- Romare Bearden, (American, 1911–1988), Circe, 1977, Collage on paper mounted to fiberboard, 15 x 9 3/8 in., Colonel Rex W. and Maxine Schuster Radsch Endowment fund purchase, No.2014.1

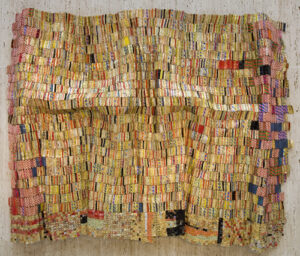

- El Anatsui, (Ghanaian, b. 1944, active in Nigeria), Danu, 2006, Aluminum, copper wire, 88 x 138 in., J. David and Laura Seefried Horsfall Endowment Fund purchase, 2006.35

- Karen LaMonte (American, b. 1967, active in Czech Republic), Kabuki, 2012, Ceramic, 51 1/2 x 28 1/2 x 35 in., John S. Lord Endowment Fund, Ineva T. Reilly Endowment Fund, and Earl O. Vits Endowment Fund purchase, 2013.17

- Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, (French, 1796–1875), Orpheus Greeting the Dawn (or Hymn to the Sun), 1865, Oil on canvas, 78 3/4 x 54 in., Gift in memory of Earl William and Eugenia Brandt Quirk, Class of 1910, by their children (E. James Quirk, Catherine Jean Quirk and Lillian Quirk Conley), 1981.136

- Rashaad Newsome, (American, b. 1979), Adwoa, 2017, Collage on paper, 20 3/4 x 16 1/2 in., Walter A. and Dorothy Jones Frautschi Endowment Fund purchase, 2018.4

- Rashaad Newsome, (American, b. 1979), Yaa, 2017, Collage on paper, 39 3/4 x 31 1/4 in., Barbara Mackey Kaerwer and Howard E. Kaerwer Endowment Fund purchase, 2018.3

- Torii Kiyotsune, (Japanese), The Actors Ichimura Uzaemon IX and Onoe Kikugoro I as Soga no Goro Tokimune and Asaina no Saburo in the Armor Pulling Scene from a Soga Play, 1760–1765, Color woodcut,310 x 141 mm, Bequest of John H. Van Vleck, 1980.2543

- Utagawa Hiroshige, (Japanese, 1797–1858), Kabuki Theaters at Nichomachi, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital, ca. 1835, Color woodcut, 225 x 343 mm, Bequest of Abigail Van Vleck, 1984.894

What do you usually tell guests about these pieces?

Rather than being a “sage on the stage,” I like to provide visitors with opportunities to engage in conversations about the artworks by asking open-ended questions. I also use tableaus, games, and drawing and writing activities to facilitate interaction with the pieces of art.

When visitors ask questions about a work, I try to share a few fun facts. For example, why Coyne began using wax as a core material in her sculptures is a fascinating story. In 1994, she took a dejected artist friend to a church in Rome, where the women lit candles and prayed for work. Their praying and lighting candles apparently succeeded. After the friend received a show, she mailed Coyne a box of candles blessed by the Pope in appreciation. Coyne made the candles into a hat for another friend. When she lit it, the whole thing caught on fire — including the friend’s hair.

Some visitors ask about the range of dates (1997-2013) on the label for Coyne’s sculpture. She is very attached to her creations and often spends more than 10 years on a piece. She began her Zelda sculpture in 1997 and completed it in 2013! In an interview, Coyne talked about how she will work intensely on a piece for a year or so and then set it aside for several years, allowing it to digest. During the interval, she continues to reflect on it. Her relationship with her artwork is also seen in her affection for the pieces. In this same interview, she continued, “I call my sculptures ‘the girls … I feel awkward about it sometimes, but they are my girls. I feel them so deeply.’”

When Coyne began sculpting, she did not title her works. In the late 1980s, an art historian suggested that because she refers to her sculptures as “her girls,” she should name them. The first piece she named was “Frida” after Frida Kahlo.

How do guests typically react to your must-sees?

Viewers remark that Coyne’s sculpture looks like a beautiful, innocent bride. Quickly, however, the burned-out candles, wax-coated silk flowers, and the statue’s downcast eyes remind them that so many marriages break up. Often someone mentions Charles Dickens’s character Miss Havisham, who was left at the altar. Time stopped for her — everything in the house stopped, nothing changed. The wedding cake stayed uneaten on the table for 30 years. She lived and eventually died in her bridal dress. The Chazen curators reinforced the “bride interpretation” by placing Louise Nevelson’s sculpture, Black Wedding Cake, next to Coyne’s piece.

Coyne welcomes viewers to create their own interpretations of her sculptures and to use her titles and names for further exploration. To culminate a conversation on Coyne’s sculpture, I often ask groups to “look for Zelda” in the work and make connections between Coyne’s sculpture and Zelda’s life.

Is there anything you’d like to pass along to readers in this difficult time about art and the solace it can provide, or about the Chazen in general?

When I conclude an “Art Comes from Art” tour, I summarize for visitors that Petah Coyne discovers inspiration in the novels she reads. Greek and Roman sculptures are Jim Dine’s muses. Romare Bearden saw confirmation of the African American experience in Homer’s The Odyssey. Karen LaMonte studies Japanese kimono fabrics and designs to spark ideas for her sculptures about women’s societal roles. These artists and many others not only illustrate interconnections among the arts but also demonstrate how we, too, can turn to all forms of art for inspiration, reflection, insights, encouragement, and hope.